new web: http://bdml.stanford.edu/pmwiki

TWiki > RisePrivate Web>StaticModeling? > FrictionAdhesionOptimization > FrictionalAdhesionPaperFigures>AnisotropicIsotropicExample2 (19 Apr 2006, DanielSantos? )

RisePrivate Web>StaticModeling? > FrictionAdhesionOptimization > FrictionalAdhesionPaperFigures>AnisotropicIsotropicExample2 (19 Apr 2006, DanielSantos? )

-- DanielSantos? - 19 Apr 2006

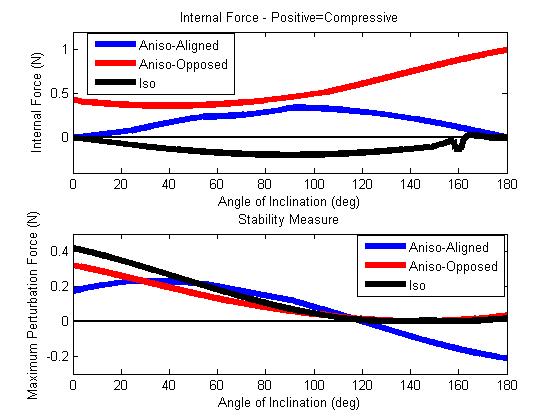

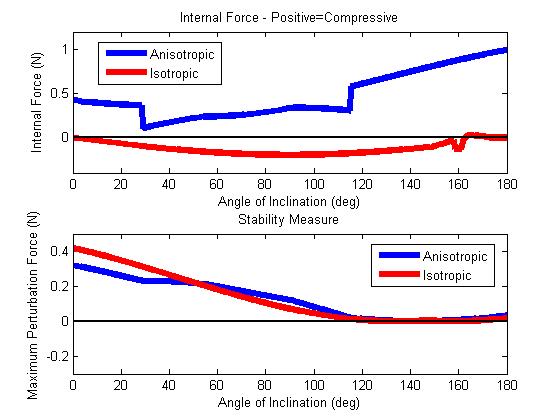

There is not much difference between the truncated isotropic model and the non-truncated isotropic model. I think that the reason we are seeing comparable amounts of "safety" between the isotropic and anisotropic cases is b/c we designed the analysis that way. We have normalized both contact models to be "critically" stable at some angle between 0 and 180 degrees. This essentially gives both models the same "amount" of adhesion to work with, so we see rougly the same amount of safety. The isotropic case requires smaller internal forces to achieve the same amount of safety compared with the anisotropic. I think this is simply because the isotropic case can support adhesion with no shear. e.g. - at 0 degrees, the isotropic case does not have to apply internal forces to generate adhesion, whereas the anisotropic does. It may be that the way we are normalizing the two cases is not really the right thing to do, but I can't think of a better alternative. I think that the difference (exactly opposite, actually) between the internal force strategies between the two cases really points out that knowing the contact constraints and controlling internal forces is essential. One thing we are trying to argue is that with the anisotropic case you can control internal forces such that at attachment/detachment the contact forces at the foot are very small. This reduces disturbance forces on the robot/animal at these transitions. To point this out, I think we can talk about the structure of the two contact models independently of the above analysis (though I do think the above points out some other important things as well). Thinking in force space, in order to "break" the static contact, we need to control the internal forces such that we move in force space from inside the convex hull of stability to a surface on the hull. In the anisotropic case, there is a point on the hull that also happens to intersect the origin (in reality, we don't know the exacty structure of the stability hull around the origin, but Kellar's experiments point to it at least being close to the origin). This is a good thing, because (if we have enough feet on the ground to control internal forces) we can move to that point in force space and detach/attach with small forces. In the isotropic case, the surface of the hull does not intersect or come close to the origin in force space. Thus, in all cases of detachment/attachment, there will be non-zero forces at the contact. In the cases of pull-off, we will get large discontinuities in the normal force which show up as disturbances on the robot/animal (stickybot). In the cases of sliding, we will get stick/slip do to adhesion and Shallamach waves (Savkoor & Briggs) which will also cause disturbances on the robot/animal. So really, maybe the benefits of having something like the anisotropic model lie mostly with the fact that its limit surface intersects or at least comes close to intersecting the origin. Then, we obviously need to control the internal forces if we want to move in force-space to that location prior to attachment/detachment, and that is where the anlaysis comes into play.

- Planar Model with 2 Contact Points, Stride Length symmetric about COM

- Mass = 50 grams

- COM Height = 2cm

- Stride Length = 10cm

- Isotropic Embedded Truncated Cone Model (mu, a1, a2)

- Mu = 1

- a1 -> chosen so that over 0 to 180 degrees, some angle is critically stable

- a1 is the maximum adhesion of the non-truncated model

- a2 -> chosen so that 180 degrees is critically stable

- Anisotropic Frictional Adhesion Model (mu, alpha, Fmax)

- Mu = 1

- Alpha = 30 degrees

- Fmax -> chosen so that over 0 to 180 degrees, some angle is critically stable

- GP1_truncated.jpg:

- GP2_truncated.jpg:

There is not much difference between the truncated isotropic model and the non-truncated isotropic model. I think that the reason we are seeing comparable amounts of "safety" between the isotropic and anisotropic cases is b/c we designed the analysis that way. We have normalized both contact models to be "critically" stable at some angle between 0 and 180 degrees. This essentially gives both models the same "amount" of adhesion to work with, so we see rougly the same amount of safety. The isotropic case requires smaller internal forces to achieve the same amount of safety compared with the anisotropic. I think this is simply because the isotropic case can support adhesion with no shear. e.g. - at 0 degrees, the isotropic case does not have to apply internal forces to generate adhesion, whereas the anisotropic does. It may be that the way we are normalizing the two cases is not really the right thing to do, but I can't think of a better alternative. I think that the difference (exactly opposite, actually) between the internal force strategies between the two cases really points out that knowing the contact constraints and controlling internal forces is essential. One thing we are trying to argue is that with the anisotropic case you can control internal forces such that at attachment/detachment the contact forces at the foot are very small. This reduces disturbance forces on the robot/animal at these transitions. To point this out, I think we can talk about the structure of the two contact models independently of the above analysis (though I do think the above points out some other important things as well). Thinking in force space, in order to "break" the static contact, we need to control the internal forces such that we move in force space from inside the convex hull of stability to a surface on the hull. In the anisotropic case, there is a point on the hull that also happens to intersect the origin (in reality, we don't know the exacty structure of the stability hull around the origin, but Kellar's experiments point to it at least being close to the origin). This is a good thing, because (if we have enough feet on the ground to control internal forces) we can move to that point in force space and detach/attach with small forces. In the isotropic case, the surface of the hull does not intersect or come close to the origin in force space. Thus, in all cases of detachment/attachment, there will be non-zero forces at the contact. In the cases of pull-off, we will get large discontinuities in the normal force which show up as disturbances on the robot/animal (stickybot). In the cases of sliding, we will get stick/slip do to adhesion and Shallamach waves (Savkoor & Briggs) which will also cause disturbances on the robot/animal. So really, maybe the benefits of having something like the anisotropic model lie mostly with the fact that its limit surface intersects or at least comes close to intersecting the origin. Then, we obviously need to control the internal forces if we want to move in force-space to that location prior to attachment/detachment, and that is where the anlaysis comes into play.

Ideas, requests, problems regarding TWiki? Send feedback